A pilot project on Bornholm demonstrates how forward-looking water recycling for agricultural use can succeed with well-established technologies. Even more importantly, it has sparked significant momentum in Denmark’s national policy debate.

High-tech solutions are not always necessary to build future-ready projects and structures for water recycling. This core idea of the WaterMan project is demonstrated in an exemplary way on the Danish Baltic Sea island of Bornholm. Here, a team led by Paulo Martins Silva, project manager at the local utility Bornholms Energi & Forsyning (BEOF), revived a technique many had forgotten: the slow sand filter (SSF).

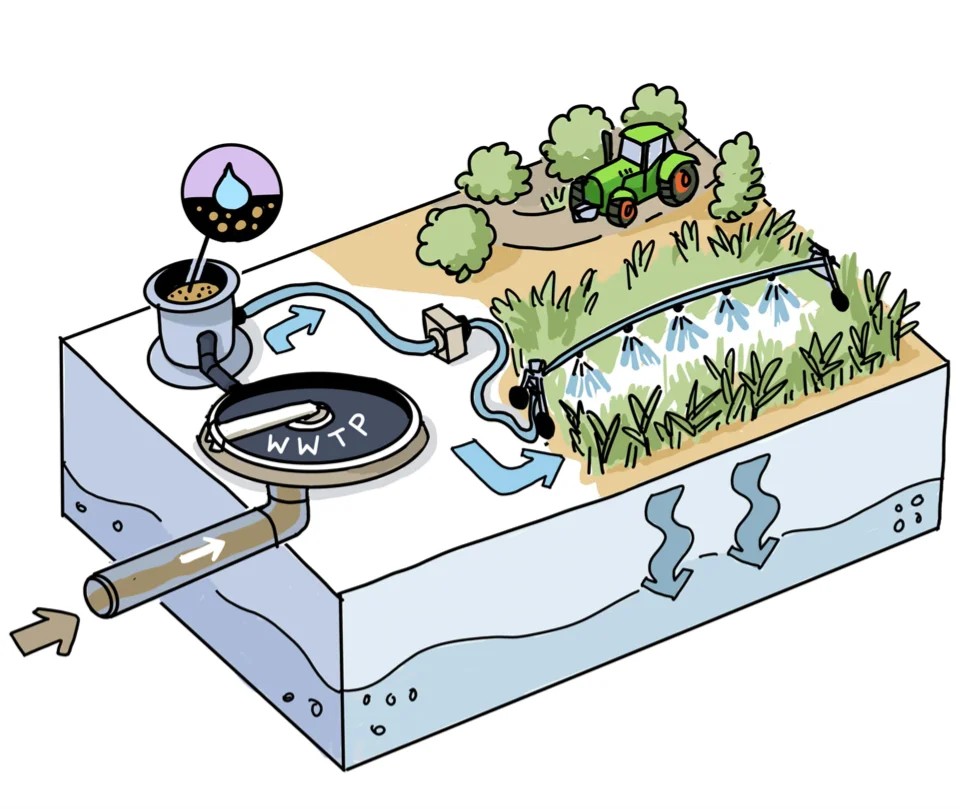

The principle is straightforward. Wastewater that has already undergone treatment at a wastewater treatment plant percolates slowly through layers of gravel and sand. The cleaning effect is strong enough that the output of the filter can be safely used to irrigate edible crops in agriculture. One visible sign of how effectively the filter works is the so-called Schmutzdecke – the biofilm that forms at the top of the sand layer. The technology originated in Germany, where the term first became established in instruction manuals from the 1970s.

“The idea to revive a slow sand filter came directly from practice,” Silva explains. “A senior colleague contributed know-how from earlier projects on artificial groundwater recharge. Building on that, we worked with the engineering consultancy Envidan to develop the design.”

Deliberately Low-Threshold – and Easy to Replicate

The BEOF team installed the sand filter next to the Svaneke wastewater treatment plant, starting with a small-scale pilot. The installation consists of a plastic cylinder about two metres high and two metres wide, filled with a 20-centimetre layer of crushed granite and an 80-centimetre layer of sand. A hose pump feeds already treated wastewater into the filter. After filtration, the water flows into an intermediate tank from which it can be drawn for agricultural irrigation. Sampling points and online sensor connections support monitoring and operation.

From the outset, the aim of the Bornholm pilot was to produce fit-for-purpose water for agricultural irrigation directly adjacent to the wastewater treatment plant, targeting EU quality class D. Key factors included short transport distances, low energy use and simple distribution options, such as tanker trucks or inexpensive PE pipes to neighbouring fields.

This low-threshold approach was intentional. Low-tech, low-cost, robust and energy-efficient – these characteristics make the SSF approach attractive for replication across the Baltic Sea Region, especially for areas wishing to move quickly from discussion to practical implementation.

With relatively little effort, slow sand filters can create new small recycling loops within the larger water cycle and make water available for agriculture during dry periods – not drinking water quality, but clean enough for irrigating edible plants or growing seeds.

A local farmer on Bornholm was immediately willing to test the sand-filtered water on open fields. “We wanted the setup to be so simple that farmers can easily understand how it works,” says Silva. “A reliable tap point with predictable quality, and clear arrangements for distribution and storage.” What happens on the fields, however, is ultimately defined by regulation.

When Regulation Blocks Practice

At this point, national politics suddenly interfered. Denmark’s Ministry of Agriculture had opted out of the EU Water Reuse Regulation, arguing that water recycling for agriculture was not relevant nationally and offered no viable business case. This removed the regulatory basis for field tests with nearby farmers.

Instead of abandoning the pilot, the team reconfigured it. A small greenhouse test bed was built next to the sand filter in cooperation with another EU project. Water from the intermediate tank is pumped into a second tank near the greenhouse and distributed via drip irrigation. This controlled environment allows validation of water quality, observation of plant responses and optimisation of system operation.

“You can’t wait until the regulatory framework is perfect,” Silva says. “In the greenhouse, we can test the recycled water safely, collect data, and show the benefits.”

Recycled Water Shows Strong Plant Growth

Spinach plants at the local Frennegaard farm were among the first crops irrigated with the recycled water. They grew well – an important proof point.

At the same time, BEOF engaged in extensive outreach with local farmers, municipal officials and regional stakeholders. A workshop organised with the farmers’ association combined a site visit to the Svaneke plant with discussions about practical and regulatory issues.

Although national policymakers had opted out of water reuse, farmers on Bornholm showed strong interest. They saw a clear business case, particularly during increasingly frequent drought periods.

“Often the psychological barrier is bigger than the technical one,” Silva notes. “Once people see the system and observe the first results, acceptance grows.”

Unexpected Gamechanger: New EU Directive

In November 2024, the new EU Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive (EU 2020/3019) was adopted. It requires water reuse to be considered whenever large wastewater treatment plants are upgraded – and member states can no longer opt out.

Denmark must now align with the new rules. Bornholm already has a functioning demonstrator, including data, technology and committed partners.

“Suddenly, everyone is talking about water reuse in Denmark again.”

The Bornholm sand filter has become a tangible reference point in the renewed national debate. While success is not yet measured in large volumes of recycled water, the pilot shows that water recycling is not a distant vision but an actionable option using existing technologies.

Not a Self-Running Solution – Many Questions Remain

Slow sand filter projects still require careful planning. Open questions include site and operating conditions, space requirements, removal rates for micro-pollutants, potential need for additional treatment stages, commissioning timelines, clogging frequency, maintenance intervals, and realistic operating costs. All depend on local context.

Nevertheless, the direction is clear.

“Water is a limited resource – even in the north,” says Silva. “The faster we add local loops, the more resilient our water supply becomes. The slow sand filter is one building block among several – but an extremely accessible one.”

This perfectly reflects the WaterMan philosophy: integrating small, pragmatic loops into the larger water cycle, sharing data, building acceptance and enabling scaling. Change starts locally – a principle strongly confirmed by the Bornholm slow sand filter pilot.

Want to Learn More?

Additional information on this Bornholm pilot measure is available in the Water Recycling Toolbox, developed within the WaterMan project:

https://www.eurobalt.org/waterrecyclingtoolbox/use-cases/bornholm-recycling-treated-wastewater-for-agricultural-use/

About the “WaterMan” project

Due to climate change, periods of drought are becoming more frequent in the Baltic Sea Region, and drinking water – mainly sourced from groundwater – can become scarce. For this reason, it will be necessary to use water of different qualities and tap into additional sources of “usable water” in the future.

WaterMan (Promoting water recycling in the Baltic Sea Region through capacity building at the local level) is implemented within the Interreg Baltic Sea Region Programme 2021–2027 and supports municipalities and water companies in adapting their strategies by developing practical solutions for water recycling and recirculation. Through region-specific approaches and real-life pilot measures, the project helps make local water supply systems more climate resilient.

More information: https://interreg-baltic.eu/project/waterman/