It is astonishing, really, that recycling swimming-pool water has never been systematically tested before. In this sense, the pilot in Braniewo – set up by the local municipal administration in cooperation with the Gdańsk University of Technology – is a true pioneering achievement, with encouraging results.

Perhaps it takes first-hand experience with prolonged drought and water scarcity for our attention to turn to all the obvious sources for water recycling. When the grass on the car park in front of the public swimming pool is already turning brown and the neighbouring sports field has to be watered constantly just to remain playable, while inside people are splashing around in thousands of hectolitres of valuable drinking water, one thing becomes clear: in times of climate change, swimming in a man-made pool could become as much of a “nice-to-have” as playing football on green turf.

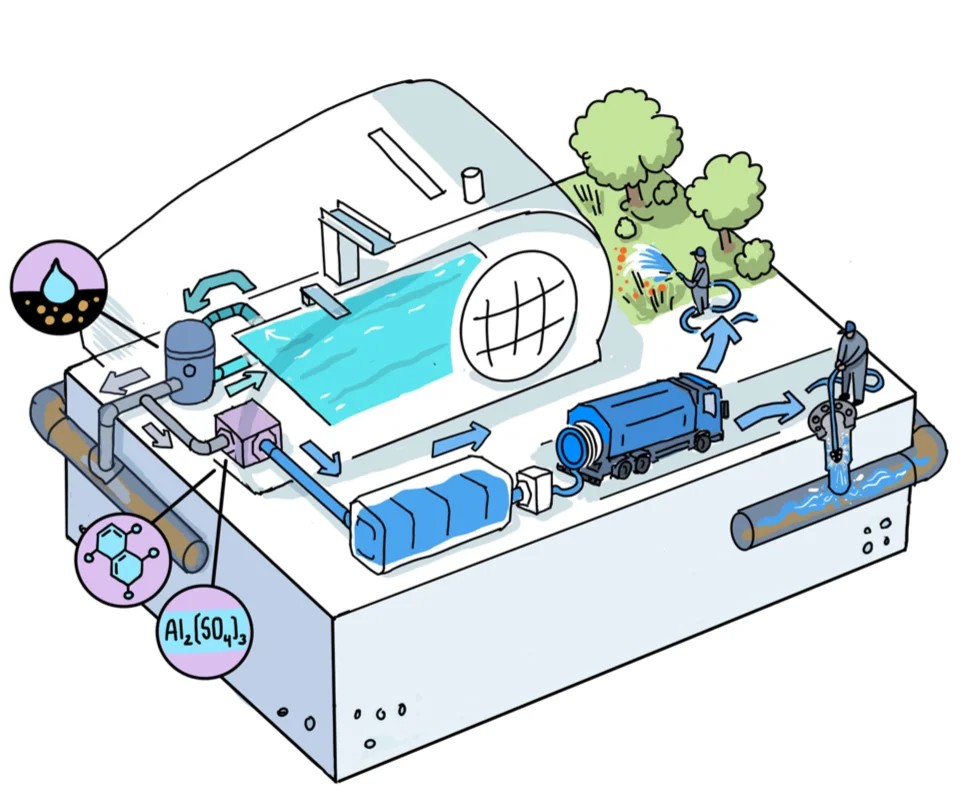

Unless, that is, we embed it sensibly in a circular water-management approach in which, after appropriate treatment, it can become a valuable resource – whether for irrigating green spaces, cleaning the municipal sewer network, or watering the adjacent sports field. In any case, for the future. Because the people of Braniewo, in Poland’s north, will continue to enjoy going for a swim.

The Discovery of a Resource

Swimming pools use large amounts of drinking water every day, which is regularly replaced or discharged during backwashing of the filters. Just as regularly, tanker trucks could pull up here to draw off this water – once treated – from a newly created reservoir and recycle it for various uses. What began as a thought experiment has, within a few years, become an ambitious real-world laboratory for water recycling.

It took an almost Herculean technical, political and legal effort to create the necessary preconditions. In doing so, Braniewo is breaking new ground at the European level as well. Even in the context of the EU Water Reuse Regulation, the reuse of swimming-pool water is still uncharted territory.

Because the basic idea sounded so compellingly simple, it was all the more surprising that, in fact, no information on similar test projects could be found anywhere. Apparently, no one had ever tried it. Yet public acceptance of recycled swimming-pool water as a resource for irrigating sports grounds and green spaces was expected to be comparatively high.

“People often struggle to accept treated wastewater. But water they use themselves when swimming seems less alien to them,” says Krzysztof Czerwionka, who oversees the project technically and conceptually on behalf of the Gdańsk University of Technology. In this respect, such a project could be an important door-opener for a more comprehensive water-recycling strategy that taps into additional sources.

Part of a Comprehensive Concept that Also Includes Knowledge Sharing

The project team soon realised just how challenging the task would be. What seemed simple at first proved riddled with pitfalls and stumbling blocks: chlorine in the water, limited space for tanks, uncertain volumes and a thicket of regulations. Sub-projects, such as blending the end product with rainwater, were tested and then dropped. What had looked like a straight path turned into a winding process of trial and error.

Once a feasible setup had been defined, the team first tested the treatment process under laboratory conditions at the Gdańsk University of Technology. The principle was straightforward: backwash water from the filtration system is collected, temporarily stored, filtered and disinfected using UV light. A dual monitoring system – manual and automated – ensured water-quality control.

Shortly after the initial lab trials, work began to install the pre-tested recycling system on a larger scale next to the filtration plant in the basement of the indoor pool. “To get the equipment into the room, we even had to enlarge the building’s gate,” recalls Jerzy Butkiewicz, the municipal official responsible for water in the Braniewo city administration. On site, he had to coordinate planning, administration, technicians and construction firms alongside day-to-day operations.

In the end, the team delivered a small but fully functional system: dechlorination tanks, UV filtration and a loop that converts utility water into a usable resource. The treated water is collected and stored in a new reservoir under the car park.

Even outside the indoor pool, it becomes clear that this pilot measure is part of a broader concept for modern water management in which education and knowledge sharing play an important role. Within the WaterMan framework, the partners have also created a rain garden on what was once a fully sealed car park. It uses the site’s natural slope to channel rainwater into planted swales and retain it longer. This allows vegetation to thrive, cools the surrounding area on hot summer days and eases pressure on the flood-prone Pasłęka River during heavy rain.

Information boards explain these links and introduce both the rain garden and the pool-water recycling pilot to visitors and school classes. Technically, the two initiatives operate as separate water cycles, yet they are connected in people’s perception – from the visible rain garden to the hidden facility beneath the asphalt.

The Real Potential Could Be Unlocked in New Pool Developments

With the system now commissioned, Braniewo can recover up to 50 percent of the water generated during backwashing. Across the entire pool operation, this translates into savings of about 15 percent of the drinking water that previously went unused down the drain.

At the same time, the pilot’s limitations are clear. Retrofitting such a system into an existing pool infrastructure requires many compromises. Much larger recycling potentials could be realised if water recycling were considered from the outset when planning and constructing new facilities.

In addition to backwash water, shower water could also be treated using the same recycling process. In existing buildings, however, shower wastewater is mixed with toilet wastewater, making separation too complex.

Why not recycle the actual pool water as well? Pool water is not ordinary wastewater: higher chlorine levels, direct contact with bathers and strict hygiene requirements make such an approach far more demanding. Backwash water, by contrast, is produced regularly, clearly defined and can be treated efficiently in a closed loop.

Not Only Technology – Trust Also Has to Be Built

Convincing people and organisations to use recycled water is another challenge. The football pitch next to the pool would be an obvious candidate for irrigation with treated swimming-pool water, but the turf supplier currently guarantees grass quality only when drinking water is used. A test run will therefore take place later.

For now, Braniewo has chosen a manageable first application: flushing water for municipal sewer cleaning. If stable operation and consistent quality can be demonstrated, further uses will be considered, including watering green spaces and potential access for private users such as allotment gardeners.

“We are planning a simple draw-off system for small users,” says Butkiewicz. “This will give citizens direct access and bring the topic into everyday life.”

A Big Long-Term Perspective

Rainwater is often only seasonally available. Pool backwash water, by contrast, is generated continuously and its quality can be closely monitored. Combined with the system’s educational value, this gives the pilot strong long-term potential.

School classes visiting the pool will gain hands-on insights into sustainable water strategies and be able to tour the installation. This makes the issue tangible and strengthens understanding of why small recycling loops are needed within the larger natural water cycle.

From Unknown Terrain to Fertile Ground

A small recycling loop now runs in the basement of Braniewo’s indoor pool. Getting there meant venturing into unknown territory and learning by trial and error.

“Pilot measures like this require patience, pragmatism and commitment,” says Butkiewicz. “But they show that sustainable change can start small and grow from there.”

What was once unfamiliar ground is now fertile soil for new ideas and projects – freshly watered with recycled filter backwash.

Want to Learn More?

Additional information on this Braniewo pilot measure is available in the Water Recycling Toolbox, developed within the WaterMan project:

https://www.eurobalt.org/waterrecyclingtoolbox/use-cases/braniewo-recycling-water-from-a-public-indoor-swimming-pool/

About the “WaterMan” project

Due to climate change, periods of drought are becoming more frequent in the Baltic Sea Region, and drinking water – mainly sourced from groundwater – can become scarce. For this reason, it will be necessary to use water of different qualities and tap into additional sources of “usable water” in the future.

WaterMan (Promoting water recycling in the Baltic Sea Region through capacity building at the local level) is implemented within the Interreg Baltic Sea Region Programme 2021–2027 and supports municipalities and water companies in adapting their strategies by developing practical solutions for water recycling and recirculation. Through region-specific approaches and real-life pilot measures, the project helps make local water supply systems more climate resilient.

More information: https://interreg-baltic.eu/project/waterman/